Climbing Mt. Humphrey

When it was time for me to arrive in Arizona to climb Humphrey’s Peak, I was a bit disappointed to have a horrible forecast the only day I could go up. The forecast was bad enough that I considered not even driving to the mountain. Perhaps I could better spend my time elsewhere in Arizona, such as Navajo Nation, or even revisit the Grand Canyons? The late afternoon had hurricane force winds of 70 mph (105 kph) which was a sure death sentence. I decided to chance my only option, which would be to try to summit around noon and get off the mountain before it got too nasty. Needless to say, the weather earlier in the day was still horrible and it was impossible to get a view of the mountain I was about to attempt. After this adventure was over, I was playing with photos on my computer and was surprised to see that not only had I seen this mountain before, I had actually photographed exactly ten years ago. This photo was taken in the early fall, before heavy snows hit the mountain.

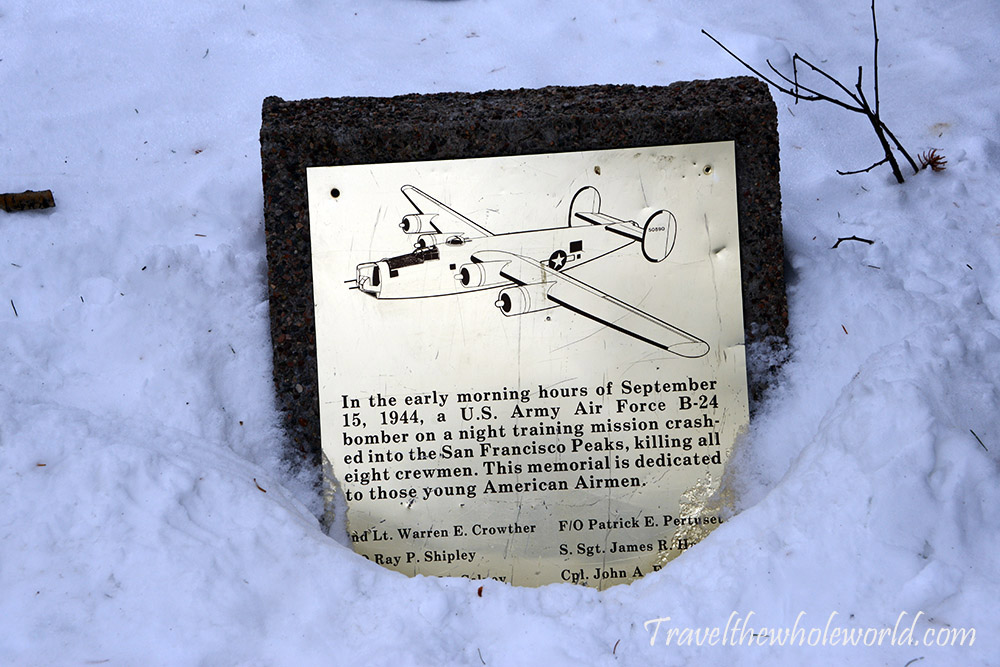

Of all the mountains I’ve ever hiked in my life, I’d say that Humphreys has by far the worst trail marker for the starting point. I’m still not even sure where I was supposed to start as I write this. Luckily I had a map on my phone and the trail looked to start around a ski lift. I didn’t see anything that looked like a hiking trail, so instead I started walking on a wide ski run. A few minutes later I saw this sign mentioning the wreckage of a B-24 in 1944. I had forgotten this story, and hoped to see the wreckage higher up on the mountain. From what most had written it seems difficult to find, even in the summer when the weather is good. This marker also suggested I was at least starting off in the right place!

After the B-24 memorial sign, I aimlessly crossed a ski run and then happened to see a marker tied to a tree. I’m still not sure how anyone would have known to cross that ski run at and hike that direction without using a map, but anyway, I was happy to be on my way! The photo above was the first I took once I was in the woods, below you can see another shot about 500 feet higher where the trees already seemed to have changed. I was seriously shocked, and even a bit mad, when I came across a sign saying that a winter permit was required. I remembered reading multiple times there were no permits or red tape required to climb this mountain. My understanding that climbing the nearby Agassiz peak was illegal due an endangered flower that lives by the summit, but even that was allowed during the winter. I wouldn’t have hesitated to get a permit had I known. At this point I was already off to a slightly late start. The last thing that was going to happen was for me go back to my car and spend an hour or two trying to find out how and where to get a permit, so off I went.

With the horrible forecast I would have been curious if they would have even given me a permit at all. So far conditions were easy like they always are down low. My understanding was it hadn’t snowed in at least a few days on the mountain. I figured the trail would be nicely packed by other climbers from the past week and the snow wouldn’t be too much of an issue. As a matter of fact, I had been more worried about snow on the roads than snow on the trail, as I heard the road can sometimes close. Just three weeks ago I had failed going up Nevada’s highest point because the roads were so bad I couldn’t even get 1,000 meters below the trailhead. For Humphreys Peak, it turns out the road only closes in the very beginning or end of winter. If there is snow on the road but not enough to open the slopes then there isn’t much motivation to bring a plow to help the one or two hikers that might show up. In the middle of winter, thousands of people come here to ski, so the road will be open 100%.

When I drove in I was in a long line of cars and thought the trail could be busy. It turned out they were all skiers and I found myself alone. I figured I’d be the only one here, but within an hour I was surprised to hear voices up ahead. To be honest, if they were heading down I almost thought to hide behind a tree if that meant avoiding a $500 fine for not having a permit. As I continued I saw that it was a group of three people heading up, definitely not rangers. We had a quick conversation where I learned that they also didn’t have permits, which made me feel morally better. They cheerfully told me they’d see me on the summit to which I replied, hopefully! The winds made me feel like there was a 50/50 chance I’d be turning around. At this altitude, I could see some rime ice that wind had built up on the trees, but conditions were great.

Being hyper focused on the winds, I ended up making the mistake of underestimating the snow. So far the trail had been nice and packed as I expected, but around 10,500 feet (3,200 meters) I encountered my first slope created by a rock slide. I had been moving at an excellent pace, and likely would have reached the summit in less than three hours if I had been able to maintain it. This slope looks pretty simple, but as I crossed it I found myself occasionally stepping into waist deep pockets of snow. I was constantly pulling myself out and cursing at the slope which should have taken a minute to cross. Instead it probably took around ten, and I figured the three other climbers had caught up and were watching while screaming with laughter. After getting across I turned back and was happy they weren’t in sight to see that shameful moment.

After I crossed the slope and got back onto the trail I had a short break with an easy trail again. Shortly there after I was mortified to find more deep snow. It was impossible to predict where the snow might hold you and where you suddenly might fall straight down to your waist.

I tried to carefully place my weight on the snow, and sometimes it worked but more often than not I’d suddenly lose my balance and find myself half buried again. It was tiring to pull myself out, and I realized this wasn’t working at all. After another 15 minutes of swimming in place I accepted defeat; this was absolutely impossible without snow shoes. I was going at a snail’s pace that’d probably all but guarantee me a deadly date with the coming wind storm. I can’t say how disappointed I was, and angry at myself for not bringing snowshoes.

On my way back a desperate idea came to me. I didn’t remember if the other three were wearing snow shoes, but if they were I had a chance to let them break trail. I expected to run into them within minutes, but after a short time it was obvious they were no longer on the trail. On another rock slide I could see footprints going off the trail and straight up the mountain. The real trail seemed to have more switchbacks than necessary as it wasn’t very steep, so I preferred this more direct route anyway. Happiness returned to my soul when I was able to start climbing at a reasonable pace. Don’t get me wrong, there were still a few occasionally deep pockets of snow, but this was a small price to pay for having a chance again. By now the rime ice on the trees was much thicker as I started to approach 11,000 feet (3,350 meters).

I still figured I’d run into the other three climbers within 15 or 20 minutes, but after 30 minutes it was clear we had gone up in different directions. By now I had no idea where the trail was. The foot prints I was following had started off with multiple people and by now seemed to be from one or two hikers. Being that I was off the trail and couldn’t even find the other three climbers, I had given up a while ago on the idea of finding the crashed B-24. You can probably imagine my surprise when I found wreckage at 11,300 feet (3,400 meters). I wasn’t even sure exactly which side of the mountain the bomber was one, so to have blindly stumbled upon it was one of those special moments in life. This bomber had crashed way back in September of 1944, where eight servicemen lost their lives. As someone who had spent years in the Marines and worked on aircraft, I had a special appreciation for those who passed away here. I spent a short time taking a break here, drinking some water and putting on my crampons before continuing.

I figured the bomber site would put me back on the trail, but I still didn’t see it can’t say I was too concerned anyway. I felt I had been doing fine in this direct route approach. Sometime later the final poor soul who had broke the trail for me must have turned around, and all footprints suddenly disappeared. By now I was close to 12,000 feet (3,650 meters), and luckily the snow was much more packed and easier to deal with. Once I started to approach the summit ridge it seemed each step I took increased the wind a notch while inversely decreasing the snow depth. Almost worse than the wind was all the rime ice. The mountain was building rime ice on everything, and it didn’t hesitate to add ice to my face or camera. I had a difficult time taking pictures from this point forward, but you can kind of see how much ice exists on the landscape here.

Just below the ridge I was now finding patches of ice and then occasionally completely exposed rocks. It was too windy here to have deep patches of snow, and although I was rapidly approaching the bad weather I felt my odds of summitting were now 75/25. Here are two more photos showing everything covered in rime ice.

It’s never a good thing to be hiking off trail, especially when you have such horrible conditions like I was in. I had felt better when I had met the other three climbers, and was certain I would see them again. I can’t imagine they came up to the first snow slope minutes after we met and immediately turned around, but otherwise I don’t see how else it was possible that I never saw them again. I still feel that they had gone up one of the rock slides and then decided to bail out once they got close to the bad weather. I can’t argue that that wasn’t a wise choice. It’s always a bit scary to be in bad weather, off trail and alone. From a distance I couldn’t tell if this was a dead tree or a trail marker, but as I got closer I saw I was back where I should be again!

Once fully up on the ridge the conditions got much worse. This was the kind of weather that was borderline climbable. The visibility was extremely poor, but the ridge made it easy to orientate myself. The winds were harsh but not strong enough that I was losing my footing. I had tried to climb two other mountains where I was literally being blown around, which of course I immediately made the obvious call to head down. The winds here were bad but not at that level yet. Plus, if things suddenly got much worse then I simply had to make a left turn off the ridge and descend down the mountain. Even in poor visibility there was no reason for me to become disoriented, but even if I did by descending in any direction it’d be a short time until I found myself in the safety of the trees and out of the wind again. With that logic I decided to cautiously continue to the summit.

Maybe as bad as the wind was still the rime ice. The final journey to the summit was in extremely poor conditions. When I reached the summit of Arizona I could hardly see the sign much less appreciate the views. I was happy to knock off another state high point. I’d be lying if I didn’t feel a bit concerned all alone on the summit with no visibility and fierce winds. It seemed like the winds were worse not exactly at the summit but maybe a few hundred feet below. Descending back into worse weather increased my fear a bit, but once I dropped off the ridge they were no longer threatening. Back at 11,500 feet (3,500 meters) there was almost no wind at all, and by 10,500 feet (3,200 meters) it was peaceful. It was almost impossible to imagine such a harsh environment on the summit just a short time ago.